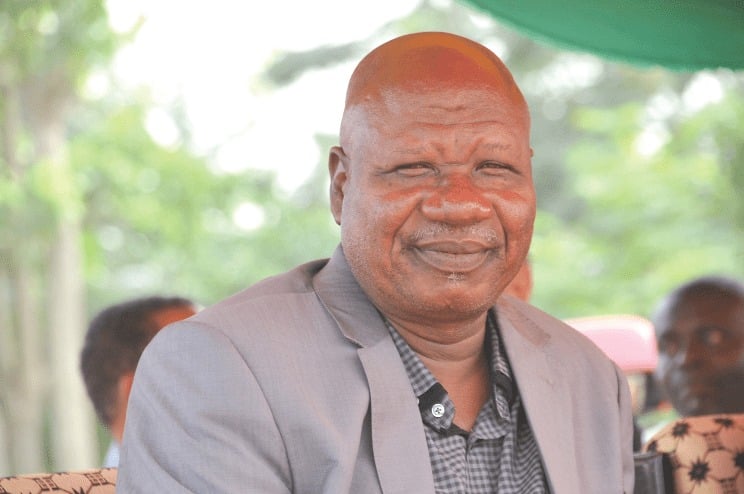

Allotey Jacobs, the former Central Regional Chairman of the National Democratic Congress (NDC), has expressed his views on the readiness of Ghana for female political leadership, drawing parallels with the recent United States elections. Jacobs referenced the defeat of former Vice President Kamala Harris, suggesting that her loss indicates a broader societal reluctance towards accepting women in leadership roles. During his appearance on the “Kokrokoo” morning show on Peace FM, he pointed out that while he personally backs the notion of a female President for Ghana, the existing political environment may not be conducive to such a radical shift.

Jacobs articulated that the outcome of the U.S. elections serves as an indicator of the prevailing attitudes towards female leaders, both in America and Ghana. He stated, “For Harris to lose the elections, America is not ready for a female President, and Ghana, too, may not yet be prepared for a female Vice President.” This perspective highlights a significant factor in political campaigns: public perception and cultural readiness for female leadership. Jacobs’ assertion suggests that societal attitudes play a crucial role in political outcomes, potentially impacting female candidates who aspire to attain high office.

The discussion surrounding Trump’s victory over Harris raises important questions within the NDC, especially in relation to Ghana’s political landscape. Jacobs cautioned party members against hastily comparing the U.S. electoral situation to Ghana’s circumstances, especially with the upcoming general elections scheduled for December 7. The implications of such comparisons could lead to misinterpretations of voter behavior and political dynamics in Ghana, which has its unique socio-political context. Jacobs emphasized the need for the NDC to critically analyze its strategies in light of these lessons from the U.S. elections.

Moreover, Jacobs’ comments reflect broader national sentiments about gender and leadership in Ghana. While he is supportive of advancing female candidates within the political sphere, his hesitation underscores the complexities involved. The reluctance to accept women in prominent political positions may stem from entrenched cultural beliefs, resistance to change, or skepticism about women’s capabilities in governance. Jacobs’ observation could thus resonate with many Ghanaians who may feel unprepared for a significant shift in leadership paradigms, echoing the sentiments observed in the U.S. election results.

In light of these observations, it is essential for political parties in Ghana, including the NDC, to take cognizance of the implications of such gender biases in their approaches to endorsements and candidate selection. Encouraging more women to take up leadership roles requires not only internal party support but also concerted efforts to change societal attitudes that hinder women from attaining high office. Jacobs’ commentary serves as a reminder of the ongoing struggle for gender equity in politics and governance, and the necessity for advocacy and educational initiatives aimed at shifting public perspectives.

In conclusion, alluding to the recent U.S. elections, Allotey Jacobs highlights the prevailing doubts surrounding female leadership in Ghana. His reflections uncover the intricate relationship between societal readiness and electoral outcomes, suggesting that Ghana may still be grappling with similar hesitations as its American counterpart. As the NDC prepares for the upcoming general elections, consideration of these dynamics could be pivotal for shaping their strategies and ensuring that they foster an inclusive political environment that empowers female politicians.