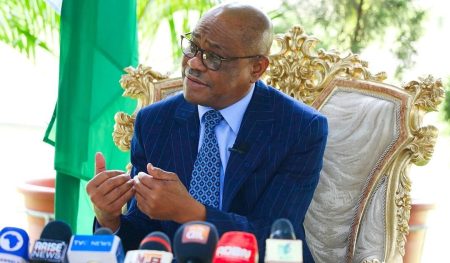

Rotimi Amaechi, a former Minister of Transport in Nigeria, delivered a scathing indictment of the country’s political landscape at a National Conference on Strengthening Democracy. His central argument, delivered with stark candor, painted a grim picture of Nigerian politics as a self-serving enterprise driven by the base motives of theft, violence, and the relentless pursuit of power. Amaechi’s assertion, “The politician is there in Nigeria to steal, to maim, to kill, and to remain in power,” resonated as a harsh truth, echoing the disillusionment and cynicism felt by many Nigerians towards their political leaders. He didn’t spare the current administration, directly referencing President Bola Tinubu and suggesting that the deeply ingrained patterns of political behavior were unlikely to change under the new leadership. He challenged the audience, accusing them of complicity through their short memories and willingness to applaud empty rhetoric, allowing politicians to “get away with murder.”

Amaechi’s critique extended beyond general accusations to encompass the very fabric of political engagement in Nigeria. He described a system riddled with transactional relationships, where political rallies are reduced to paid performances and loyalty is bought and sold. He shared anecdotes from his own experience, recounting instances where attendees at political rallies were motivated solely by monetary incentives, readily switching allegiances depending on who offered the highest payment. This transactional nature, he argued, undermines the very foundation of democratic participation, reducing citizens to mere props in a cynical power play. His anecdote about a rally where attendees, initially paid to support Jonathan, were later swayed by Tinubu’s offer highlights the fleeting and superficial nature of political support in such a compromised system.

Furthermore, Amaechi’s personal narrative added another layer of complexity to his critique. He admitted to being a part of the system he condemned, attributing his involvement to the pressures of poverty. This confession, while potentially undermining his moral authority, lends a certain authenticity to his perspective. He presented himself not as an outsider pointing fingers, but as someone entangled within the web of Nigerian politics, speaking from firsthand experience. His claim of being indispensable to the APC’s formation and electoral victory further underscores his intimate knowledge of the inner workings of the political machinery. This insider’s perspective lends weight to his pronouncements, suggesting a deep understanding of the dynamics he criticizes.

Amaechi’s comments sparked a reaction from former Vice President Atiku Abubakar, who shared his own anecdote about a rally where attendees left abruptly after their paid time expired. This exchange, while brief, further highlighted the transactional nature of political gatherings, reinforcing Amaechi’s central point. It illustrated the pervasive understanding within political circles of this practice, suggesting it is not an isolated incident but rather a systemic issue. The fact that both Amaechi and Abubakar, representing different political factions, acknowledged this reality underscores the widespread acceptance of these transactional practices within the Nigerian political landscape.

Amaechi’s assertions, while undeniably provocative, raise crucial questions about the state of Nigerian democracy. His depiction of a political class driven by self-enrichment and power, operating within a system where citizens are reduced to paid participants, paints a bleak picture. The implication is that genuine democratic participation, driven by informed choices and genuine support, is severely compromised. This raises concerns about the legitimacy of political representation and the ability of the system to effectively address the needs of the people. If political engagement is primarily transactional, it stands to reason that the interests of the electorate are secondary to the self-serving agendas of the political elite.

Ultimately, Amaechi’s pronouncements serve as a wake-up call, demanding a critical examination of the values and practices that underpin Nigerian politics. His critique challenges the narrative of progress and democratic consolidation, forcing a confrontation with the uncomfortable realities of corruption, manipulation, and the erosion of public trust. While his personal involvement in the system he criticizes may raise questions about his motives, it also lends credence to his observations. His words, however controversial, serve as a stark reminder of the deep-seated challenges that continue to plague Nigerian democracy and the urgent need for reform. The question remains: will his words spark genuine introspection and action, or will they be dismissed as the cynical pronouncements of a disillusioned insider?