The sands of Egypt have yielded another secret, a royal tomb lost for millennia. British archaeologists, led by Professor Piers Litherland of the University of Cambridge, have unearthed the final resting place of Pharaoh Thutmose II, a ruler of the illustrious 18th Dynasty who reigned approximately 3,500 years ago. This remarkable discovery, located roughly 2.4 kilometers west of the famed Valley of the Kings in Luxor, brings to a close the longstanding enigma surrounding the pharaoh’s burial site. The tomb, designated “C4,” lies in an area traditionally associated with the interment of royal women, a surprising location that challenged previous scholarly assumptions, which placed the tomb within the vicinity of the Valley of the Kings. The discovery underscores the vast archaeological potential that remains hidden within the ancient Egyptian landscape.

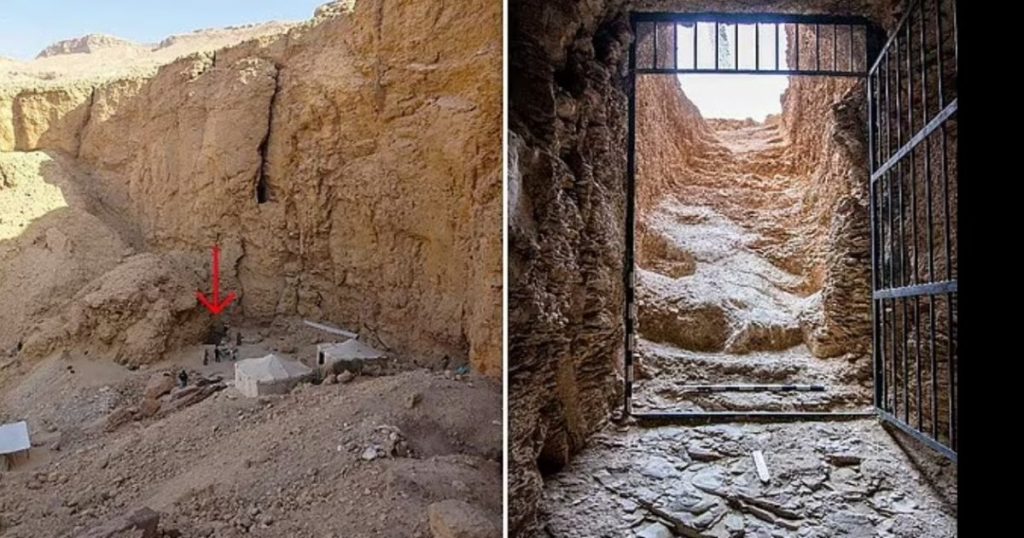

The journey to uncovering Thutmose II’s tomb began in 2022 with the identification of a rock-cut staircase at the base of a cliff. This unassuming entrance, which initially hinted at the tomb of a royal consort rather than a pharaoh, led to a grand descending corridor. The size and grandeur of the doorway and staircase, however, quickly suggested a discovery of greater significance. Progress was initially hampered by the tons of sand and limestone debris that choked the passage, the remnants of ancient floods that had ravaged the tomb over centuries. The team, undeterred, persevered with their meticulous excavation, eventually gaining access to the main burial chamber.

Inside, the team was met with the telltale signs of royal burial. The ceiling, painted a vibrant blue and adorned with yellow stars, a motif exclusively reserved for pharaohs, confirmed the chamber’s royal occupant. Further evidence lay in the wall decorations, which depicted scenes from the Amduat, a sacred text accessible only to the kings of Egypt. These pictorial narratives, meant to guide the pharaoh’s soul through the perilous journey of the afterlife, cemented the tomb’s regal identity. Fragments of alabaster jars, inscribed with the title “deceased king” alongside the name Thutmose II and his wife, Hatshepsut, provided the final, irrefutable proof.

Ironically, unlike the dazzling treasures that filled Tutankhamun’s tomb, the resting place of Thutmose II was devoid of riches and even the pharaoh’s mummy. The absence of these expected elements points to a dramatic past. The devastation wrought by ancient floods is believed to have necessitated the relocation of the pharaoh’s remains. Historians believe they were moved to the Deir el-Bahri royal cache, a hiding place discovered in the 19th century where numerous royal mummies were found. A mummy, believed at the time to be Thutmose II, was among those discovered. This mummy, however, was in a severely deteriorated state, with damage to the body and a severed right arm, a testament to the turbulent times that followed the pharaoh’s death.

Recent research has cast doubt on the identification of the Deir el-Bahri mummy as Thutmose II. The remains are estimated to belong to a man over the age of 30, while historical records suggest Thutmose II died before reaching that age. This discrepancy has reignited the debate about the pharaoh’s true remains and the circumstances surrounding his death. Scholars hypothesize that he may have succumbed to disease, as the embalmed body found at Deir el-Bahri exhibited signs of an illness that even the meticulous mummification process could not fully erase. The mystery surrounding the pharaoh’s demise adds another layer of intrigue to the newly discovered tomb and the ongoing investigation into the life and death of Thutmose II.

Thutmose II’s reign, though relatively short, played a significant role in the trajectory of the 18th Dynasty. Estimates of his reign vary between 13 years (1493–1479 BCE) and a mere three years (1482–1479 BCE). Regardless of its length, his rule fell within the golden age of the 18th Dynasty, a period widely regarded as the zenith of Ancient Egyptian civilization. This dynasty, spanning over two centuries (circa 1539–1292 BCE), produced some of Egypt’s most renowned figures, including the powerful female pharaoh Hatshepsut, who was Thutmose II’s wife and successor, Amenhotep I, and the boy-king Tutankhamun. The discovery of Thutmose II’s tomb provides an invaluable opportunity to further understand this pivotal period in Egyptian history and the lives of the pharaohs who shaped it. The empty tomb, while lacking the immediate spectacle of gold and artifacts, offers a wealth of information about royal burial practices, religious beliefs, and the challenges faced by ancient Egyptians in preserving their heritage against the ravages of time and nature.