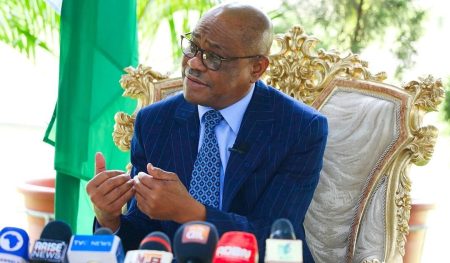

Dr. Omar Touray, President of the ECOWAS Commission, embarked on a high-level visit to the Nigeria-Benin Republic border post, a crucial artery for trade and movement within West Africa. His assessment was stark: despite significant investment, critical infrastructure like scanners, lighting systems, and bridges lay idle, hindering the region’s free movement agenda. Touray expressed his disappointment at the neglect, emphasizing the responsibility of member states to maintain ECOWAS-funded infrastructure. He stressed that while ECOWAS initiates these projects, the upkeep falls squarely on the individual nations. The visit underscored a critical disconnect between regional aspirations for integration and the on-the-ground realities of neglected facilities and bureaucratic obstacles.

A key concern raised by Touray was the proliferation of checkpoints along the corridor, which contradicts the spirit of free movement. These multiple customs and immigration stops not only cause delays and frustration for travelers but also create breeding grounds for corruption. He called for greater transparency and accountability, urging officials to clamp down on unrecorded payments demanded from citizens. Touray emphasized that while free movement is a cornerstone of regional integration, it does not equate to a lack of regulation. He underscored the importance of valid identification for travel, balancing security concerns with the facilitation of movement. While acknowledging the challenges, he expressed optimism about the joint commitment from Nigeria and Benin to improve cross-border cooperation, emphasizing the need for swift action to realize the border’s potential.

Ben Oramalugo, the Nigerian Customs Controller at the Seme border, painted a bleak picture of the operational difficulties. He revealed that essential scanners remained non-functional since his arrival in February, hampering the detection of contraband and posing a security risk. The lack of adequate lighting in the pedestrian passage created an unsafe environment at night, while the absence of basic amenities like roofing and running water further compounded the challenges. The reliance on Benin for electricity, a precarious arrangement leaving the Nigerian side vulnerable to power outages, highlighted the lack of essential infrastructure on the Nigerian side. Oramalugo also pointed to inconsistencies in economic policy, particularly double taxation of goods in transit, as a deterrent to trade. The cumulative effect of these infrastructural and policy shortcomings underscored the urgency of reform.

Oramalugo’s concerns extended beyond infrastructure. He highlighted the language barrier between Nigerian and Beninese officials as a major impediment to effective cooperation, advocating for compulsory bilingual education within ECOWAS to prepare future generations for cross-border collaboration. He reiterated the urgency of repairing the broken scanners and improving the pedestrian crossing’s safety. Furthermore, he proposed limiting the number of checkpoints along the corridor to a maximum of three, asserting that the current state of the road reflected poorly on Nigeria’s image. These operational bottlenecks, ranging from security risks to basic amenities, painted a picture of a border post struggling to fulfill its function.

Further illustrating the dire situation, a walkthrough of the Nigerian inspection facility revealed a leaking roof that had damaged computer equipment, a problem reported but unresolved. The tour also highlighted the lack of interoperability between the biometric systems of Nigeria and Benin, rendering the Nigerian system redundant for cross-border checks. This disconnect in technological implementation underscored the need for harmonized systems to achieve true integration. The testimonies of transport drivers added a human dimension to the challenges, revealing the everyday realities of extortion, harassment, and delays faced by those traversing the border. These firsthand accounts exposed the gap between policy pronouncements and the practical experiences of those navigating the system.

Joseph Dibang, a commercial driver, recounted the ordeal of navigating multiple checkpoints, with each stop presenting an opportunity for unofficial payments. The lack of receipts for these payments highlighted the lack of transparency and accountability. While transport companies attempted to enforce documentation requirements, some passengers still traveled without valid identification, posing security risks and forcing drivers to negotiate with immigration officials. A Beninese driver echoed these sentiments, pointing out that ECOWAS decisions were often disregarded at the ground level, leading to inconsistencies in implementation and hefty fines for compliant vehicles. These accounts emphasized the need for stronger enforcement of ECOWAS protocols and a crackdown on corrupt practices. Touray acknowledged the inconsistencies, reiterating the ECOWAS commitment to both security and seamless trade while condemning extortion. The call for intensified public awareness campaigns on the ECOWAS free movement protocol highlighted the importance of educating both citizens and officials about their rights and responsibilities. The ambassador’s comments underlined the significance of the Seme border as a barometer for the success of ECOWAS’s free movement agenda. The visit served as a crucial reality check, bringing to light the urgent need for comprehensive reforms to bridge the gap between regional aspirations and the practical realities at the border. The establishment of a Presidential Task Force to dismantle multiple checkpoints signaled a potential turning point in addressing the challenges along this vital corridor.