Enugu State has officially withdrawn from a lawsuit involving several states challenging the laws related to the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) and the Nigerian Financial Intelligence Unit (NFIU) Guidelines. This move makes Enugu the sixth state to opt out of the lawsuit, which has been marked by multiple withdrawals since its inception. The initial three states to withdraw prior to a Supreme Court hearing were Anambra, Adamawa, and Ebonyi, all of which made their decisions known on October 22, when the case was scheduled for arguments. Following this, Benue and Jigawa state joined the trend, formally applying for withdrawals on October 23 and 24, respectively. This series of withdrawals indicates a growing trend of dissent among the plaintiffs regarding the continuation of the legal challenge.

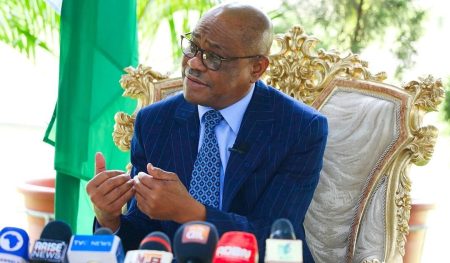

The Attorney General of Enugu State, Kingsley Udeh, communicated the withdrawal through an application directed to the Supreme Court, which was received officially by the apex court on October 24, 2024. The withdrawal was documented in a suit tagged SC/CV/178/2023, where it was explicitly noted that Enugu intended to discontinue its role as a plaintiff. The legal notice included formal language indicating Udeh’s intention to withdraw the state’s lawsuit against the Attorney General of the Federation, thereby solidifying Enugu’s position in the ongoing legal dispute. This formal withdrawal suggests a possible reassessment of the lawsuit’s viability or a strategic decision to distance the state from a case that could yield unfavorable consequences.

The lawsuit had commenced with Kogi State leading the charge against the EFCC in 2023, eventually drawing the involvement of 18 other states, including Enugu. With Enugu’s exit, the number of states still pursuing the legal battle has dwindled to 13. Central to the plaintiffs’ argument is a reliance on a Supreme Court ruling in the case of Joseph Nwobike vs. the Federal Republic of Nigeria, which they claim established an important constitutional precedent. Specifically, they assert that the ruling found that the United Nations Convention Against Corruption was improperly incorporated into the EFCC Establishment Act due to non-compliance with constitutional guidelines laid out under Section 12 of the 1999 Constitution (as amended).

The plaintiffs highlight that Section 12 requires prior approval from a majority of the state Houses of Assembly for conventions to be adopted into Nigerian law, a stipulation they argue was neglected during the enactment of the EFCC Act in 2004. By failing to adhere to this process, the plaintiffs claim that the Act lacks legitimacy, making the institutions established under its authority effectively illegal. This contention aligns with their assertion that not all states ratified the underlying convention, thereby rendering any law that emerged from this flawed process inapplicable to those states that did not approve it.

As the case continues with fewer parties involved, the ramifications of these withdrawals may impact the remaining states’ strategy and the dynamics in the courtroom. The six withdrawn states signal a potential lack of unity and consensus among the plaintiffs, leading to questions about the strength of the legal arguments still being presented by the remaining states. The evolving situation reflects ongoing tensions concerning the EFCC’s mandate and authority, highlighting broader concerns about legal compliance, state rights, and the interplay between federal and state jurisdictions in Nigeria. The judicial outcomes of this case may have long-lasting implications, not only for the EFCC and its current practices but also for the future consideration of similar constitutional challenges across the nation.