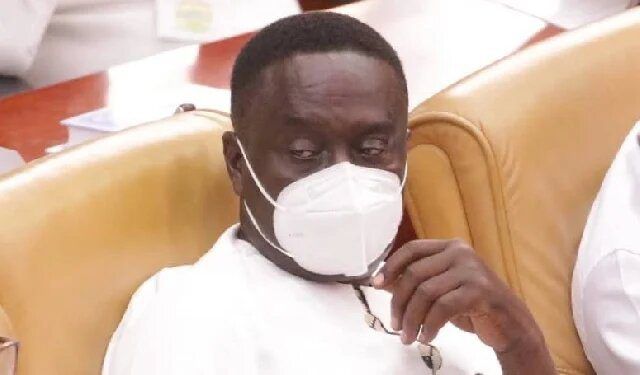

James Gyakye Quayson, the Member of Parliament for Assin North in Ghana’s Central Region, has pointedly criticized the role of foreign banks in the Ghanaian and broader African financial landscape. He argues that these institutions, rather than fostering economic growth, impose burdensome conditions that stifle local businesses and hinder development. Central to his critique are the exorbitant interest rates charged by these banks, often ranging from 20% to 30%, creating a stark contrast with the significantly lower rates, around 5%, offered by the same banks in Western countries. This disparity, Quayson argues, effectively transfers wealth from African businesses to boost Western economies. He contends that the stringent collateral requirements demanded by these foreign banks, often limited to land or real estate, further restrict access to capital for budding entrepreneurs, creating an uneven playing field that favors established businesses.

Quayson’s critique delves into the inherent power imbalance between foreign banks and African economies. He posits that these banks, operating within a globalized financial system, dictate terms and conditions that are disadvantageous to local businesses. These terms, structured to maximize profit repatriation to their headquarters, often disregard the unique challenges faced by African entrepreneurs, particularly in accessing affordable credit. The high interest rates, according to Quayson, effectively erode the profit margins of local businesses, preventing reinvestment and expansion, and thereby limiting their contribution to economic growth and job creation. This creates a vicious cycle of financial dependence, where African economies remain reliant on external capital while simultaneously being drained of their resources through high interest payments.

The argument extends beyond mere profit maximization. Quayson suggests that the operations of foreign banks in Africa reflect a broader pattern of economic exploitation, mirroring historical patterns of resource extraction. By charging significantly higher interest rates than they do in their home countries, these banks effectively transfer wealth from African economies to Western ones. This exacerbates existing inequalities and contributes to the underdevelopment of the African financial sector. Moreover, the stringent collateral requirements further disadvantage African businesses, often forcing them to put up vital assets, creating a precarious situation where business failure could lead to significant personal losses. This risk aversion, instilled by the demanding lending practices of foreign banks, further stifles innovation and entrepreneurship.

Quayson’s critique also highlights the systemic nature of the problem. He argues that the operating model of foreign banks in Africa is designed to extract maximum value, often at the expense of long-term sustainable development. The focus on short-term profits, coupled with a lack of understanding of the local context, results in lending practices that are often ill-suited to the needs of African businesses. This creates a systemic disadvantage, hindering the growth of local industries and reinforcing existing economic disparities. The lack of accessible and affordable credit also limits the ability of African economies to diversify and develop value-added industries, thereby perpetuating dependence on raw material exports and further entrenching them in a cycle of unequal exchange.

The comparison with interest rates in Western countries serves to underscore the inherent unfairness of the system. The fact that the same banks offer significantly lower rates in developed economies highlights the double standard applied to African borrowers. This differential treatment, according to Quayson, reflects a deeper bias embedded within the global financial system, where African economies are perceived as higher risk and therefore deserving of less favorable terms. This perception, often based on outdated stereotypes and a lack of understanding of the dynamic and growing African markets, perpetuates a cycle of underinvestment and limited access to capital. The result is a self-fulfilling prophecy, where the perceived high risk translates into higher interest rates, which in turn stifles growth and reinforces the perception of risk.

Ultimately, Quayson’s argument calls for a fundamental re-evaluation of the role of foreign banks in African economies. He advocates for a more equitable and sustainable financial system that prioritizes the needs of local businesses and fosters long-term economic development. This may involve greater regulation of foreign banks, the promotion of local financial institutions, and the development of alternative financing mechanisms that are more attuned to the specific challenges and opportunities present in African markets. His call for change is not merely a critique of foreign banks, but a broader appeal for a more just and equitable global financial system that empowers African economies to reach their full potential. He envisions a future where African businesses have access to the same affordable credit enjoyed by their Western counterparts, fostering innovation, job creation, and sustainable economic growth across the continent.