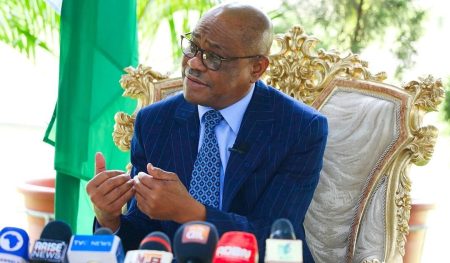

Udengs Eradiri, the Labour Party’s governorship candidate in the last Bayelsa State election, recently resigned from the party, citing deep disillusionment with the political landscape and the pervasive influence of money in Nigerian politics. He entered the race with the conviction that the electorate yearned for genuine leadership and good governance, but his experience on the campaign trail proved otherwise. He witnessed firsthand the prioritization of immediate financial gain over long-term development and the willingness of voters to compromise their values for monetary inducements. This “see and buy” phenomenon, as he described it, shattered his idealistic vision of a populace eager for transformative leadership. He found that the electorate, particularly in his own village, was readily swayed by cash handouts, undermining the integrity of the electoral process. Eradiri’s campaign, lacking the financial resources to compete with established political players, became a victim of this transactional system. He felt that the electorate’s focus on immediate financial gratification overshadowed any consideration of his track record or vision for the state’s future.

Further exacerbating Eradiri’s disappointment was the perceived betrayal by his own party. He accused the Labour Party leadership of financial impropriety, claiming they had withheld campaign funds and engaged in negotiations with the ruling party, effectively undermining his candidacy. Eradiri alleged that the party leaders demanded substantial sums of money in exchange for their support, highlighting the pervasive nature of transactional politics in the state. He also pointed to inconsistencies in the party’s handling of similar allegations of financial misconduct in other states, suggesting a lack of transparency and accountability within the Labour Party itself. The financial burden of the campaign fell squarely on his shoulders, with limited support from the party. Even a late contribution from Peter Obi, the party’s presidential candidate, was insufficient to offset the financial disadvantages he faced. Eradiri’s experience exposed the stark reality that in Bayelsa’s political landscape, financial resources often dictate electoral outcomes, leaving candidates with limited means at a significant disadvantage.

Eradiri’s observations extend beyond the immediate circumstances of his campaign, touching upon the deeper systemic issues plaguing Bayelsa’s political and economic development. He questioned the focus on resource control, particularly oil revenue, arguing that it has become a distraction from the true potential of the state’s diverse resources. He believes that the preoccupation with oil wealth has overshadowed the development of other sectors, such as agriculture and tourism, which could offer more sustainable and equitable growth. He criticized the prevailing political culture in which former governors wield disproportionate economic and political power, limiting opportunities for younger, less affluent candidates. This concentration of wealth and influence, he argued, creates an environment where opposition is stifled and genuine competition is difficult to achieve. His own campaign, he contends, became a bargaining chip in this political game, further solidifying his conviction that the system is rigged against those without access to substantial financial resources.

Despite the setbacks and disappointments, Eradiri maintains a strong belief in the importance of service and integrity in public office. He contrasts his own record as a commissioner, where he claims to have prioritized service over personal gain, with the conduct of other politicians who prioritize self-enrichment. He points to his tenure as both Commissioner for Youth and Commissioner for Environment, asserting that he effected positive change from within the system, demonstrating that principled leadership is possible even in a compromised environment. He argues that the focus should be on serving the people, with the “pecks of office” being secondary considerations, rather than the primary motivator. He points to his clean record, devoid of any allegations of corruption, as evidence of his commitment to ethical leadership.

Looking ahead, Eradiri is taking time to reassess the political landscape and chart his future course of action. While acknowledging the inherent challenges of opposition politics in Bayelsa, particularly for those without significant financial backing, he remains committed to serving the people of the state. He recognizes the importance of political timing and the unwritten rules of rotational politics in Bayelsa, noting that his decision to contest the last election was partly driven by the fact that it was his senatorial district’s “turn.” He understands the complexities of these political calculations and how they influenced the outcome of the previous election, acknowledging the role they will likely play in future contests.

Eradiri’s resignation from the Labour Party, coupled with the exodus of other party members, underscores his disillusionment and the widespread dissatisfaction with the party’s leadership. He pointed out that many key positions within the state’s Labour Party structure were occupied by government appointees, raising questions about the party’s independence and commitment to genuine opposition. He believes this compromised structure contributed to the party’s failure in the last election. The collective resignation signals a potential shift in the political landscape and the possibility of a new political alignment forming in the lead-up to the next governorship election. Eradiri’s emphasis on conviction and his refusal to compromise his values, even in the face of immense pressure, suggest that he will continue to be a force in Bayelsa politics, albeit perhaps on a different platform.