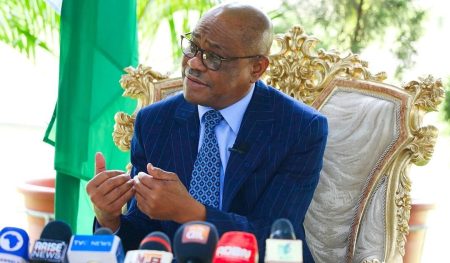

Nigeria’s power sector faces a critical challenge in meeting the nation’s burgeoning energy demands. Professor Barth Nnaji, former Minister of Power, emphasizes the stark reality that Nigeria requires a monumental leap in its power generation capacity, needing at least 100,000 megawatts (MW) of readily available power to fuel its industrial ambitions, propel economic development, and satisfy the energy needs of its rapidly expanding population. This figure dwarfs the current installed capacity, highlighting the significant infrastructural deficit that plagues the sector. Nnaji underscores that merely installing generation capacity is insufficient; the power must be readily available to consumers. The existing transmission infrastructure is woefully inadequate to handle this required volume, representing a major bottleneck in the power delivery chain. This critical gap underscores the urgent need for comprehensive upgrades and expansion of the transmission network to effectively distribute the increased power generation.

The newly introduced National Integrated Electricity Policy, while promising on paper, faces the daunting challenge of effective implementation. Nnaji stresses that the success of this policy hinges on a multifaceted approach that prioritizes aggressive expansion of power generation capacity, significant upgrades to the transmission infrastructure, and the implementation of cost-reflective tariffs. These tariffs must strike a delicate balance between affordability for consumers and ensuring sufficient revenue for power sector operators, thereby attracting investment and reducing the financial burden on the government. The enormous debt accrued by the government, primarily stemming from non-cost-reflective tariffs, underscores the unsustainable nature of the current pricing model. A sustainable power sector requires a pricing structure that ensures the financial viability of all stakeholders, from generation companies (GenCos) to distribution companies (DisCos).

Nnaji advocates for a pragmatic approach to the policy’s execution, recognizing that a well-structured framework alone is not enough. Strategic investments in generation, transmission, and distribution are crucial for translating the policy’s objectives into tangible outcomes. He highlights the critical link between reliable electricity supply and a sustainable pricing system. Nnaji firmly asserts that electricity, a fundamental driver of economic activity, comes at a cost, emphasizing the need for a cost-reflective pricing model. Such a model would not only ensure the financial viability of the power sector but also attract much-needed investments to expand capacity and improve service delivery. This balanced approach will enable the sector to function efficiently and sustainably, ultimately benefiting both consumers and investors.

The proposition of banning solar panel imports to stimulate local production raises concerns about Nigeria’s current manufacturing capacity. Nnaji expresses skepticism about the nation’s preparedness for such a drastic measure, arguing that a transition period is crucial to allow the domestic industry to develop the necessary capacity to meet national demand. While acknowledging the merits of promoting local production, he warns against a sudden ban, which could backfire and exacerbate the existing energy deficit. A phased approach, offering incentives for local manufacturing while gradually reducing reliance on imports, would be a more prudent strategy. This would allow the domestic solar industry to grow organically and competitively, ultimately ensuring a sustainable supply of solar panels within the country.

Nnaji advocates for a balanced energy mix that leverages Nigeria’s abundant natural gas reserves alongside renewable energy sources. He cautions against viewing renewable energy as an immediate solution to the nation’s power challenges, recognizing the significant investments and infrastructure development required for large-scale renewable energy integration. He emphasizes the need to capitalize on the readily available natural gas resources by building gas-fired power plants, providing a more immediate and reliable source of electricity. This pragmatic approach recognizes the limitations of relying solely on renewables in the short term and emphasizes the importance of utilizing existing resources to meet the nation’s immediate energy needs.

In conclusion, addressing Nigeria’s power crisis requires a comprehensive and multifaceted approach. Expanding generation capacity to at least 100,000 MW, coupled with corresponding investments in transmission infrastructure, is paramount. Implementing cost-reflective tariffs is essential to ensure the financial viability of the power sector and attract crucial investments. While promoting local manufacturing is a laudable goal, a cautious and phased approach is needed to avoid disrupting the supply chain and exacerbating the energy deficit. Finally, leveraging Nigeria’s abundant natural gas resources alongside strategic investments in renewable energy offers a balanced and pragmatic pathway towards achieving energy security and driving sustainable economic growth. A well-executed National Integrated Electricity Policy, underpinned by these key elements, is essential for unlocking Nigeria’s vast economic potential and meeting the energy needs of its growing population.