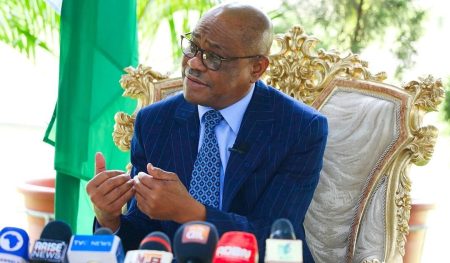

Nana Ohene Ntow, the Director of Elections Planning and Coordination for the Movement for Change, passionately advocates for integrity as the fundamental bedrock upon which national progress is built. He argues that Ghana’s current challenges are not solely the result of systemic flaws, but are significantly exacerbated by the lack of integrity within the existing structures. He contends that even with the current system, if individuals operating within it were committed to integrity, the nation’s situation would be significantly improved. Ntow emphasizes that a government grounded in integrity is not merely a desirable quality, but a prerequisite for meaningful and effective reforms. He believes that such a government would be more responsive to the needs of the citizenry, more efficient in its operations, and more likely to generate genuine and sustainable progress. This focus on integrity, he suggests, should precede and inform any larger structural changes.

Ntow’s assertion highlights the vital role of individual character and ethical conduct in public service. He believes that placing individuals with unwavering moral compasses in positions of power will organically lead to a more just and prosperous society. This, he argues, is more fundamental than simply reforming structures or rewriting laws. A system, however well-designed, can be easily corrupted if implemented by individuals lacking in integrity. He stresses that a true transformation requires a shift in mindset, a commitment to ethical principles, and a rejection of corrupt practices at every level of government. This emphasis on personal responsibility underscores the belief that integrity is not merely a political slogan, but a lived value that must be embodied by those entrusted with public office.

The core of Ntow’s argument rests on the belief that prioritizing integrity creates a foundation of trust between the government and the governed. This trust, he argues, is essential for fostering civic engagement, promoting public cooperation, and facilitating the implementation of effective policies. When citizens believe that their leaders are acting with integrity, they are more likely to support government initiatives, adhere to regulations, and actively participate in the nation-building process. Conversely, a lack of integrity erodes public trust, leading to cynicism, apathy, and ultimately, instability. Ntow posits that a government perceived as corrupt cannot effectively govern, regardless of the sophistication of its policies or the resources at its disposal.

Furthermore, Ntow suggests that a focus on integrity can catalyze a broader cultural shift within Ghanaian society. By demanding integrity from public officials, citizens are also implicitly demanding it from themselves and from each other. This creates a virtuous cycle, where ethical conduct is not merely expected of leaders but becomes a societal norm. He challenges Ghanaians to introspect and consider their own role in demanding accountability and transparency. This call for collective responsibility reinforces the idea that good governance is not solely the responsibility of those in power, but a shared undertaking requiring the active participation of all citizens.

Ntow acknowledges the complexities of achieving such a fundamental shift in governance. He poses a crucial question to the Ghanaian populace: Are they prepared to demand and uphold this level of integrity from their elected officials? He implies that true reform requires not just structural changes but a fundamental change in societal expectations and values. This interrogation challenges citizens to examine their own complicity in accepting or overlooking corrupt practices and to actively participate in creating a culture of accountability. He emphasizes that a government of integrity cannot exist without a citizenry equally committed to those principles.

However, while advocating for a fundamental shift towards integrity-driven governance, Ntow also acknowledges the potential for incremental improvements within the existing system. He suggests that even without radical overhauls, meaningful progress can be achieved through focused reforms and a renewed commitment to ethical conduct. This pragmatic approach recognizes that systemic change is a gradual process and that immediate improvements can be made while working towards larger, long-term goals. He encourages a combination of both immediate action within the current framework and a long-term vision for a more fundamentally reformed and integrity-focused government. This dual approach suggests that progress can be achieved on multiple fronts simultaneously, maximizing the potential for positive change.