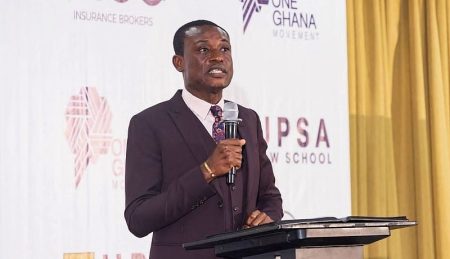

Ghana, like many developing nations, has long grappled with the pervasive issue of corruption, a debilitating force that has hampered its progress and undermined public trust. Recognizing the urgent need to address this challenge, the Office of the Special Prosecutor (OSP) was established as a dedicated institution to combat corruption and promote accountability. Kissi Agyebeng, Ghana’s Special Prosecutor, has vehemently argued that the OSP, despite facing criticisms and challenges since its inception, represents the nation’s most potent weapon in this fight. He believes that by strengthening the OSP and enshrining its independence, Ghana can effectively tackle this deep-rooted problem and pave the way for sustainable development.

Agyebeng’s central argument hinges on the OSP’s unique position and capabilities in confronting corruption. He contends that the office, with its specialized mandate, powers, and reach, possesses the necessary tools to investigate and prosecute corruption cases effectively. He emphasizes the importance of moving beyond focusing on individual personalities holding the office and instead concentrating on building the institution itself to ensure its longevity and effectiveness. This perspective underscores a critical aspect of institutional reform: the need to establish systems that transcend individual biases and political influences, thus guaranteeing their sustained functionality and impact regardless of who occupies the position. Agyebeng, therefore, advocates for solidifying the OSP’s foundation, enabling it to operate autonomously and impartially in pursuing justice.

A core component of Agyebeng’s vision for a robust OSP is its constitutional entrenchment. He proposes incorporating the office into Ghana’s constitution, thereby providing it with the highest level of protection and insulation from political interference. This constitutional backing, he argues, would not only secure the OSP’s independence but also enhance its authority and mandate. Currently, the OSP’s existence is tied to an Act of Parliament, making it susceptible to potential revisions or even dissolution by future administrations. By enshrining it in the constitution, the OSP would gain an immutable status, safeguarding its continuity and reinforcing its ability to operate free from external pressures. This, Agyebeng believes, is crucial for fostering public trust and ensuring the OSP’s effectiveness in tackling corruption without fear or favour.

Furthermore, Agyebeng advocates for expanding and strengthening the OSP’s powers and mandate. He emphasizes the need for the office to have the necessary authority to investigate and prosecute corruption cases thoroughly and efficiently. This includes not only investigative powers but also the requisite resources – both financial and human – to carry out its functions effectively. A more empowered OSP, he argues, would be better equipped to pursue complex corruption cases, unravel intricate networks of illicit activities, and bring perpetrators to justice. This enhanced capacity would not only deter potential corruption but also bolster public confidence in the justice system’s ability to address this pervasive problem.

However, Agyebeng acknowledges a prevailing paradoxical sentiment within Ghana: while there is broad public support for combating corruption, there seems to be a reluctance to fully empower the very institution designed to achieve this goal. He highlights this contradiction by stating that “everyone wants the Special Prosecutor to do his job. Yet no one wants the Special Prosecutor to do his job.” This seemingly contradictory stance, he suggests, stems from the discomfort that arises when investigations target individuals or groups within established power structures. This resistance, whether conscious or unconscious, underscores the inherent challenges in fighting corruption, as it often requires challenging entrenched interests and disrupting the status quo. This observation highlights the inherent difficulties in reforming deep-rooted systems because vested interests often resist changes that threaten their positions of power.

In conclusion, Agyebeng’s vision for an effective anti-corruption mechanism in Ghana centres on a strengthened and independent OSP, constitutionally protected and empowered to pursue its mandate without fear or favour. He believes that such an institution is essential to tackling the decades-long problem of corruption that has hindered Ghana’s development. His call for reform reflects a broader recognition of the need to move beyond superficial changes and embrace fundamental institutional reforms that address the root causes of corruption. By enshrining the OSP’s independence, expanding its powers, and fostering a genuine public commitment to fighting corruption, Ghana can create a more transparent and accountable governance system, laying the foundation for sustainable development and a more equitable future. The success of the OSP, however, hinges not only on its structural and legal framework but also on a collective societal will to confront corruption and support the institutions designed to combat it.