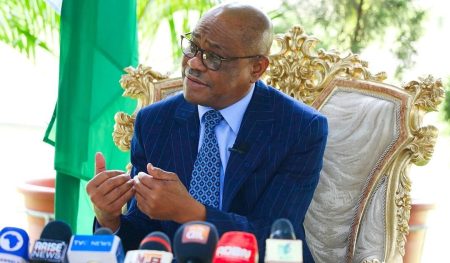

Afolabi Akindele, CEO of Adamakin Investment & Works Limited, asserts that a vast majority, 90%, of buildings in Lagos lack mortgage insurance, a critical component for a robust and secure housing market. This deficiency stems from the absence of registered titles for most properties, a prerequisite for viable mortgage insurance. He highlights the irony of this situation by referencing the historical land ownership of Madam Tinubu, whose title, dating back to 1912 and registered in 2008, remains embroiled in controversy. Akindele alleges that the Lagos State Government, under Governor Babajide Sanwo-Olu, has placed an embargo on the title due to political motivations and the self-serving interests of corrupt officials. He argues this action deprives the state of substantial revenue generation potential and disregards the historical significance of Madam Tinubu’s land ownership.

Akindele emphasizes the legitimacy of his involvement, citing an irrevocable power of attorney and a Memorandum of Understanding with the Tinubu family, solidifying his authority over the estate. He decries the pervasive land grabbing and illegal acquisition that plagues Lagos, blaming corrupt government officials and politicians for exploiting the lack of proper records. He accuses these individuals of preying on families and profiting from the wealth accumulated by Madam Tinubu. Akindele further alleges that attempts to challenge the family’s ownership have been thwarted, even resorting to manipulating historical records in the Ibadan and British archives. He asserts that the Tinubu family’s claim is legally sound and incontestable, challenging anyone with conflicting claims to present their evidence.

Akindele contends that the Tinubu estate encompasses significant land holdings within Lagos, including the disputed Magodo land, where he claims the affected parties are merely tenants with no legitimate ownership rights. He dismisses any government decisions contrary to the family’s claim as irrelevant, insisting that only the Supreme Court can overturn their ownership. This stance highlights the complex and often contentious nature of land ownership in Lagos, where historical claims, political maneuvering, and allegations of corruption often intertwine.

Olufemi Oyedele, CEO of Fame Oyster & Co., concurs with Akindele’s assessment of the lack of mortgage insurance in Lagos. He attributes this not to the absence of registered titles, but to the rudimentary nature of the mortgage system in Nigeria. He explains that most Lagos residents finance their properties without mortgage loans, thus negating the need for mortgage insurance. Oyedele points out that mortgage insurance is primarily designed to protect lenders in cases of borrower default, particularly when down payments are less than 20% of the purchase price. He acknowledges that while mortgage insurance increases the overall cost of a loan, it plays a crucial role in enabling borrowers to access financing they might otherwise be denied.

Akindele further criticizes the government’s tax reforms, arguing that they offer little benefit to the real estate sector. He suggests that a more effective approach would be for each state to maintain comprehensive records of registered land and property ownership. This, he believes, would unlock significant revenue potential for both state governments and financial institutions. He contends that the federal tax system undermines the ability of states to generate revenue independently, particularly in a state like Lagos with its vast real estate holdings.

In summary, the crux of the issue revolves around the lack of mortgage insurance in Lagos, stemming from either the absence of registered land titles or the underdeveloped mortgage system. This situation, compounded by allegations of corruption, political interference, and land grabbing, creates a volatile and uncertain environment for property ownership in Lagos. The Tinubu estate serves as a microcosm of these larger issues, highlighting the challenges and complexities of navigating land ownership in a rapidly developing urban environment. The contrasting perspectives of Akindele and Oyedele offer different diagnoses of the problem, but both point to systemic issues within the Nigerian real estate and financial sectors that need urgent attention.