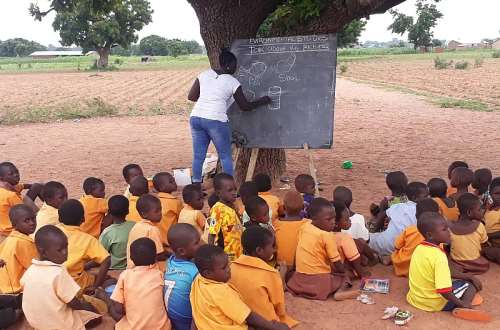

Kofi Asare, the Executive Director of Africa Education Watch, has highlighted a significant disparity in Ghana’s education system, revealing that a staggering 80% of “schools under trees” – educational institutions lacking proper infrastructure – are concentrated in the northern regions of the country. This alarming statistic underscores the deep educational divide between the north and the rest of Ghana, where access to quality education remains a persistent challenge. This geographical imbalance extends beyond mere infrastructure, affecting other critical aspects of education such as furniture provision and teacher availability. The northern regions also bear the brunt of the deficit in school desks, with over 80% of the estimated one million desks needed concentrated in these areas, further compounding the challenges faced by students and educators in these regions. This lack of basic resources creates an environment that is not conducive to effective learning and perpetuates the cycle of educational inequality.

The stark reality of the teacher shortage further exacerbates the educational crisis in the north. Asare pointed out that until recently, Central Gonja alone faced a severe shortage of teachers, with approximately 80% of the required teaching positions for primary and kindergarten levels remaining unfilled. This acute shortage deprives children of consistent instruction and guidance, hindering their academic progress and limiting their future opportunities. The lack of qualified teachers not only impacts the quality of education but also places an additional burden on existing educators, who are often stretched thin trying to cater to large classes with limited resources. This dire situation underscores the urgent need for targeted interventions to address the teacher deficit and ensure equitable access to quality education across all regions.

The consequences of this educational disparity manifest clearly in the Basic Education Certificate Examination (BECE) results, a crucial assessment marking the completion of basic education. The pass rates in the deprived northern districts lag significantly behind the national average, painting a stark picture of the unequal opportunities available to students in these regions. Asare noted that while the national BECE pass rate might be around 80%, the pass rate in these underserved districts often hovers around 60%, a substantial 20% difference that reflects the cumulative impact of inadequate infrastructure, resource shortages, and teacher deficits. This performance gap reinforces the need for focused interventions to bridge the educational divide and ensure that students in all regions have an equal chance to succeed.

The concentration of educational challenges in the northern regions highlights the systemic inequalities that persist within Ghana’s education system. The “schools under trees” phenomenon, the lack of basic furniture, and the severe teacher shortage all contribute to a learning environment that is far from conducive to academic achievement. This situation perpetuates a cycle of disadvantage, limiting the opportunities available to children in these regions and hindering their potential to contribute meaningfully to society. Addressing this complex issue requires a multifaceted approach that prioritizes investment in infrastructure, teacher recruitment and training, and resource allocation to ensure that all students, regardless of their geographical location, have access to quality education.

The issue of educational inequality became a prominent topic during the recent election campaigns, with the National Democratic Congress (NDC) arguing that the previous government’s flagship Free Senior High School (Free SHS) policy had diverted funding away from critical areas within the education sector, particularly basic education. This assertion highlights the ongoing debate surrounding resource allocation within the education system and the potential trade-offs between different levels of education. While the Free SHS policy has undoubtedly expanded access to secondary education, concerns remain about its impact on the quality of education at both the secondary and basic levels. The NDC’s argument suggests that a re-evaluation of funding priorities may be necessary to ensure that resources are distributed equitably across all levels of education, addressing the pressing needs of both basic and secondary schools.

With the appointment of Haruna Iddrisu as the new Minister of Education, the challenges facing the education sector, particularly in the northern regions, are expected to take center stage. The issue of “schools under trees,” the shortage of desks and teachers, and the disparity in BECE pass rates will likely be high on his agenda. Mr. Iddrisu’s leadership and policy decisions will be crucial in determining the future direction of education in Ghana and whether the government can effectively address the deep-seated inequalities that continue to plague the system. The nation will be watching closely to see how the new administration tackles these pressing issues and works towards creating a more equitable and accessible education system for all Ghanaian children.