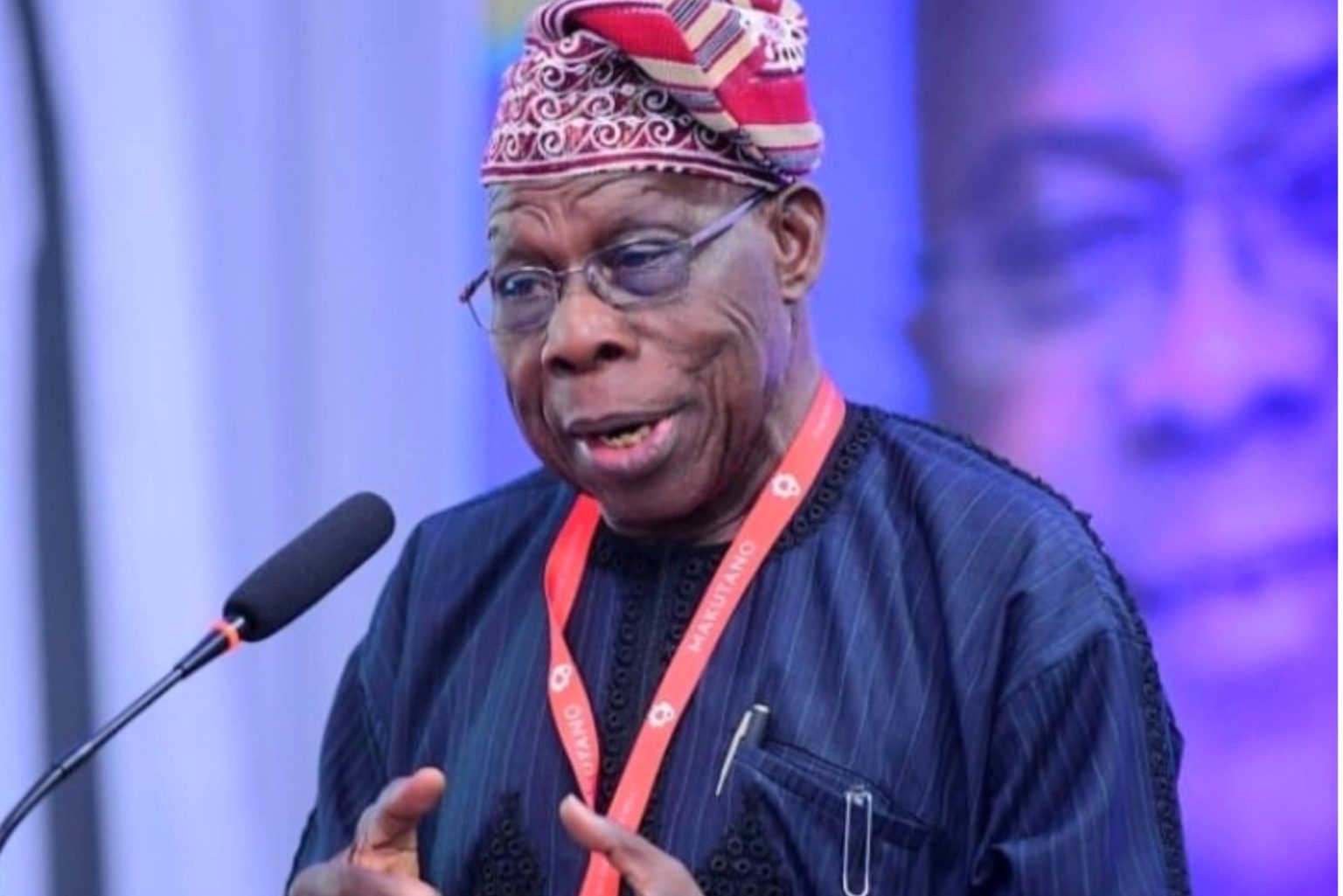

Former Nigerian Attorney General, Abubakar Malami, has vehemently refuted corruption accusations leveled against him by former President Olusegun Obasanjo. Obasanjo, in his recent book, “Nigeria: Past and Future,” alleges widespread corruption during the Buhari administration, implicating Malami as a key facilitator. The book specifically highlights the controversial presidential pardons granted to former governors Joshua Dariye and Jolly Nyame, convicted of embezzlement, as prime examples of Malami’s alleged corrupt influence. Obasanjo claims Malami orchestrated these pardons, based on false claims of ill health, for personal financial gain, and with the complicity of then-President Buhari. He depicts Malami as a central figure in a system rife with corruption, accusing him of manipulating the system for his own benefit.

Malami, however, categorically denies these allegations, emphasizing the established legal framework surrounding presidential pardons. He underscores the role of the Presidential Advisory Committee on Prerogative of Mercy, not the Attorney General, in recommending pardons. Malami explains that his role was limited to presenting the committee’s findings to the Council of State, absolving himself of direct responsibility for the decisions made regarding the pardons. He argues that the responsibility for the pardons rests solely with the committee that recommended them, not with him as the presenter of their report. This clarification aims to distance himself from the accusations of undue influence and corrupt dealings in the pardon process.

Furthermore, Malami criticizes the prevalence of unsubstantiated corruption allegations against public figures, both domestically and internationally. He cites examples of unfounded accusations against even respected figures like former President Obasanjo himself, referencing a contentious international media interview. Malami stresses the importance of providing concrete evidence and specific details to support claims of corruption. He argues that vague accusations lack credibility and are often driven by malicious intent.

To substantiate his point, Malami outlines the necessary elements for a credible corruption allegation, including specifics about the alleged bribe, the parties involved, the method of transaction, and the date and time of the alleged offense. He insists that without such particulars, allegations remain baseless and unfit for legal action. This rigorous standard, according to Malami, is essential to protect public officials from unfounded and potentially damaging accusations, ensuring that accountability is based on verifiable evidence.

The clash between Obasanjo’s accusations and Malami’s defense highlights the complexities of combating corruption within Nigeria’s political landscape. Obasanjo’s narrative paints a picture of systemic corruption enabled by high-ranking officials, while Malami emphasizes due process and the need for evidence-based accusations. The contrasting perspectives raise questions about the efficacy of anti-corruption efforts and the challenges of holding powerful individuals accountable.

The controversy surrounding the pardons granted to Dariye and Nyame, and Malami’s alleged role, underscore the ongoing debate about transparency and accountability in governance. The differing accounts necessitate further investigation and scrutiny to determine the veracity of the claims and counterclaims. The public discourse surrounding these allegations underscores the need for robust mechanisms to address corruption and uphold the rule of law. The absence of clear evidence and detailed particulars leaves room for speculation and fuels mistrust in public institutions. The exchange between Obasanjo and Malami ultimately serves as a reminder of the intricate challenges in tackling corruption and ensuring good governance.