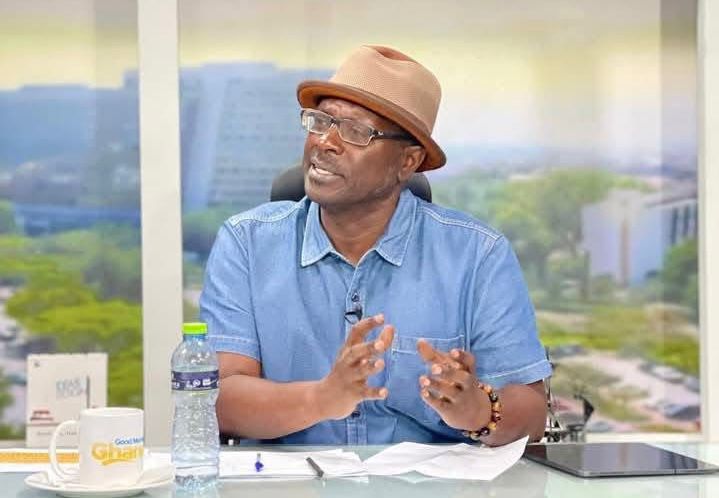

The New Patriotic Party (NPP), a major political force in Ghana, has found itself embroiled in controversy following the announcement of exorbitant nomination fees for its upcoming flagbearer contest. Professor Stephen Kwaku Asare, a prominent legal scholar and social commentator widely known as Prof Azar, has vehemently criticized the party’s decision, arguing that the steep fees create an insurmountable barrier for potential candidates who lack significant financial resources. With nomination forms pegged at GH₵100,000 and filing fees set at a staggering GH₵500,000, the total cost of entry, excluding a yet-to-be-determined “development fee,” reaches GH₵600,000. Prof Azar contends that this effectively transforms the contest into an auction, favoring the wealthy and well-connected while excluding competent and committed individuals who may not have access to such substantial funds. This, he argues, undermines the very foundations of democratic principles within the party and the broader political landscape.

Prof Azar’s critique centers on the fundamental disconnect between the exorbitant fees and the qualities required for effective leadership. He argues that the ability to raise or possess significant wealth does not necessarily translate to merit, competence, or a genuine commitment to serving the public. Instead, he posits that the high fees incentivize candidates to rely on patronage networks or seek financial backing from individuals or groups who may later exert undue influence, creating a breeding ground for transactional politics. This, he fears, will perpetuate a cycle where public office becomes a means to recoup campaign investments rather than a platform for selfless service and genuine representation of the people’s interests.

The implications of such a system, according to Prof Azar, extend beyond the immediate confines of the NPP’s internal affairs. He argues that by effectively pricing out a significant portion of potential candidates, the party undermines its own legitimacy and erodes democratic values. The message conveyed, he suggests, is that access to political leadership is contingent on financial capacity rather than merit or public trust. This creates a system where political positions are effectively “bought” rather than earned through demonstrated competence and commitment to public service. Furthermore, the exclusionary nature of the fees disproportionately impacts marginalized groups, including youth, women, and reformers, who are less likely to have access to the required financial resources.

Prof Azar’s concerns extend to the potential long-term damage this system could inflict on Ghana’s political landscape. He warns that the emphasis on financial capacity in political contests fuels a culture of transactional politics, where political favors and appointments are traded for financial contributions, ultimately eroding public trust and undermining the integrity of governance. He emphasizes the need for a system that prioritizes merit and public service over wealth and connections, allowing for a more diverse and representative political field.

In light of these concerns, Prof Azar calls for urgent intervention by the Electoral Commission to regulate internal party processes, particularly in the realm of political financing. He proposes specific measures such as capping nomination fees, eliminating development fees altogether, and exploring alternative mechanisms for ensuring candidate commitment, such as refundable deposits or signature thresholds. These measures, he believes, would level the playing field, allowing qualified candidates from diverse backgrounds to participate in the political process without being unduly burdened by exorbitant fees.

Ultimately, Prof Azar’s critique serves as a call for a broader national conversation on party reform and political financing in Ghana. He stresses that democracy should not be reduced to a “pay-to-play” system where political office is accessible only to the highest bidders. He urges a shift towards a more inclusive and meritocratic system that values competence, commitment to public service, and genuine representation of the people’s interests above financial capacity. This, he argues, is essential not only for the health of individual political parties but also for the overall strengthening of democratic values and the promotion of good governance in Ghana.