The Plight of Outsourced Workers in Nigeria’s Financial Sector: A Deep Dive into Precarious Employment

The Nigerian financial sector, a cornerstone of the nation’s economy, faces a growing crisis concerning the treatment of its outsourced workforce. The National Union of Banks, Insurance, and Financial Institution Employees (NUBIFIE) has sounded the alarm, revealing that a mere 1.5% of outsourced staff transition to permanent positions, a stark indicator of the precarious nature of these jobs. This revelation sheds light on the exploitative practices prevalent within the industry, where a significant portion of the workforce is trapped in a cycle of temporary contracts, devoid of job security, career progression, and equitable compensation. This situation not only undermines the livelihoods of thousands of workers but also raises concerns about the long-term stability and ethical foundations of the financial sector itself.

Data from the National Bureau of Statistics paints a grim picture. As of September 2020, a staggering 42.11% of employees in the banking sector, encompassing commercial, merchant, and non-interest banks, were on contract. This reliance on a contingent workforce has become deeply entrenched, with NUBIFIE’s figures indicating that out of a total workforce of 91,681 in October 2024, a staggering 68,300 were outsourced junior staff. This disproportionate number highlights the systematic preference for a flexible, low-cost labor pool over a stable and fairly compensated workforce. This preference perpetuates a two-tiered system, where core staff enjoy the benefits of permanent employment, career advancement opportunities, and significantly higher salaries, while outsourced workers are relegated to a second-class status, trapped in a cycle of temporary contracts with limited prospects.

The disparity in compensation is particularly egregious. NUBIFIE reveals that outsourced workers often earn as little as N75,000 per month, while core staff performing the same tasks receive approximately N260,000, a difference that underscores the inherent inequity of the system. This vast pay gap not only creates economic hardship for outsourced workers but also fosters resentment and a sense of injustice, potentially impacting morale and productivity within the sector. The argument often used by banks and insurance companies to justify this disparity revolves around age, with institutions claiming outsourced workers become "over age" after a few years of service, effectively barring them from permanent positions. This practice appears to be a thinly veiled excuse to maintain a low-wage workforce and avoid the obligations associated with permanent employment.

The implications of this exploitative system extend beyond individual workers and impact the broader economy. A workforce characterized by insecurity and low wages is less likely to contribute to economic growth and development. Furthermore, the lack of career progression and training opportunities for outsourced workers limits the development of skilled labor within the financial sector, potentially hindering its long-term competitiveness. The current model effectively creates a class of "working poor" within a vital sector of the Nigerian economy, contributing to social inequality and undermining the potential for inclusive growth.

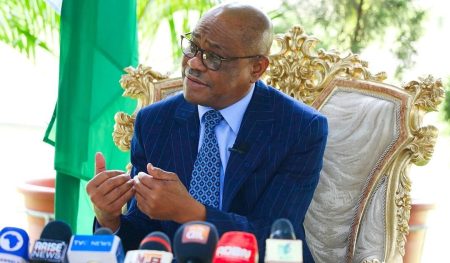

The government has recognized the need for intervention, with the previous administration unveiling guidelines aimed at improving working conditions for contract and non-permanent workers in financial institutions. These guidelines, titled ‘Labour Administration Issues in Contract Staffing/Outsourcing Non-Permanent Workers in Banks, Insurance, and Financial Institutions,’ were a step towards addressing the issue. However, their implementation and effectiveness remain uncertain, particularly given the low conversion rate of outsourced staff to permanent positions. The challenge lies in translating these guidelines into tangible changes in employment practices and ensuring their enforcement. This requires a concerted effort from all stakeholders, including the government, financial institutions, and labor unions, to create a more equitable and sustainable employment landscape.

The situation calls for a fundamental shift in the mindset of financial institutions. They must move away from viewing outsourced workers as a disposable commodity and recognize them as valuable contributors to the sector’s success. A fairer and more sustainable approach would involve offering clear pathways to permanent employment, providing adequate training and development opportunities, and ensuring equitable compensation for all workers, regardless of their employment status. This requires a commitment to ethical labor practices, transparent hiring processes, and a genuine effort to foster a more inclusive and equitable work environment. The future of Nigeria’s financial sector depends on addressing this issue and creating a system that values and invests in all its workers, not just a privileged few.