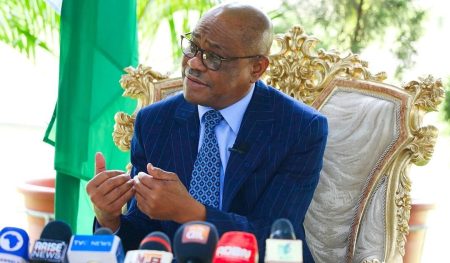

The historical leadership of the Awori kingdom in Ogun State, Nigeria, has become a subject of contention between two prominent traditional rulers, the Olofin of Ado-Odo and the Olota of Ota. The dispute arose from claims made by the Olota, Oba Abdulkabir Obalanlege, asserting his position as the Chairman of the Awori Obas Forum and implying his authority over other Awori Obas. This assertion has been vehemently challenged by the Olofin of Ado-Odo, Oba Olusola Lamidi-Osolo, who argues that the Olota’s historical subordination to the Alake of Egbaland disqualifies him from claiming such a leadership role. The Olofin emphasizes the rich and independent history of Ado-Odo, which has never been subjugated under Egba rule, unlike Ota. This fundamental difference in their historical trajectories forms the crux of the disagreement.

The Olota’s claim of superiority rests partly on the assertion that the Olota stool was the only existing traditional authority in the area until the creation of the Ifo stool in 1972. He attributed the perceived decline in the conduct of some traditional rulers to the proliferation of monarchical stools. However, the Olofin counters this argument by highlighting the historical precedence of the Ado-Odo kingdom. He cited Ado-Odo’s prominent role in the Western Region’s House of Chiefs during the regional government era, where the Olofin served as Vice Chairman, second only to the Ooni of Ife. This positions Ado-Odo as a significant power within the traditional hierarchy, independent of and arguably superior to the Olota stool, whose installation requires the approval of the Alake of Egbaland.

The Olofin’s argument is further strengthened by historical accounts detailing Ado-Odo’s resistance to Egba dominance. He referenced several historical sources, including the coronation pamphlet of the current Alake of Egbaland, which acknowledges Ado-Odo’s resilience against Egba forces. Works by S.B. Biobaku and J.F. Ade Ajayi and Crowther further corroborate this narrative, portraying Ado-Odo as a formidable obstacle to Egba expansion. Conversely, historical records indicate that Ota was conquered by the Egbas in the 19th century, placing it firmly under Egba dominion. This historical subjugation, according to the Olofin, undermines the Olota’s claim to leadership over the Awori kingdom, especially over a kingdom like Ado-Odo that has historically maintained its independence.

The Olofin also underscores the difference in the relationship between each kingdom and the Alake of Egbaland. He pointed to the historical fact that the Olota of Ota required permission to directly approach the Alake until the mid-18th century, and direct rule from the Alake only began in 1900. This reinforces the narrative of Ota’s subservient relationship with the Alake, contrasting sharply with Ado-Odo’s independent standing. The Olofin asserts that while the Awori Obas Forum serves as a platform for interaction and communication with the government, it does not grant any inherent leadership authority, especially not to a monarch whose lineage is marked by historical subordination to the Alake.

Further solidifying his argument, the Olofin presented archival evidence from 1917 recognizing the Oba of Ado-Odo as a crowned chief in the Western Province. This recognition, granted by the colonial administration, further legitimizes the Olofin’s claim of historical prominence and authority within the Awori kingdom. He contests the Olota’s right to claim leadership of the Awori kingdom, highlighting the inherent contradiction of a monarch under Egba control seeking to preside over a historically independent kingdom. The Olofin asserts that such a claim is not only historically inaccurate but also disrespectful to the traditions and history of the Awori people.

In conclusion, the dispute over the leadership of the Awori kingdom revolves around contrasting historical narratives. The Olota of Ota bases his claim on his perceived role as Chairman of the Awori Obas Forum and the historical precedence of the Olota stool. However, the Olofin of Ado-Odo vehemently rejects this claim, citing Ado-Odo’s historically independent status, its prominent role in the regional government, and archival evidence supporting its recognition as a crowned chiefdom. The historical subjugation of Ota to the Alake of Egbaland serves as a key point of contention, with the Olofin arguing that it disqualifies the Olota from claiming leadership over the entire Awori kingdom, especially over a kingdom like Ado-Odo that has consistently resisted Egba dominance. This historical debate underscores the importance of understanding the complex power dynamics and historical relationships within the Awori kingdom and its surrounding regions.