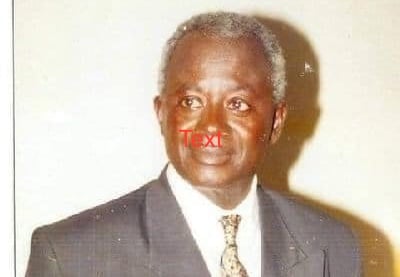

Professor Albert Adu Boahen, a prominent figure in Ghanaian history and the New Patriotic Party’s (NPP) first presidential candidate in the 1992 elections, holds a significant place in the country’s political landscape. His role as a co-founder and chairman of the Movement for Freedom and Justice was instrumental in Ghana’s transition to democracy. While his 1992 presidential bid, where he garnered over 1.2 million votes (30.29%), was unsuccessful against Jerry John Rawlings of the National Democratic Congress (NDC), it marked a crucial step in solidifying the nascent multi-party system. Adu Boahen’s initial success within the NPP was evident in his victory in the 1992 primaries, where he convincingly outperformed other contenders, including John Agyekum Kufuor. However, the political tide turned in the lead-up to the 1996 elections, with Kufuor securing the NPP’s nomination as the flagbearer, a shift that has prompted speculation and analysis over the intervening years.

The transition in NPP support from Adu Boahen to Kufuor between the 1992 and 1996 elections has been a subject of discussion, with some attributing the change to factors beyond political strategy and performance. However, Razak Kojo Opoku, a leading NPP member and Founding President of the UP Tradition Institute, vehemently refutes suggestions that Adu Boahen’s loss of the party’s nomination in 1996 was influenced by tribalism, religious prejudice, or regional biases. Opoku emphasizes that the NPP’s internal selection process has consistently prioritized merit and the perceived ability to win national elections, rather than considerations based on identity. He points to the party’s history of selecting candidates from various backgrounds, highlighting that success within the NPP is earned through demonstrating the capacity to lead the party to victory.

Opoku’s argument centers on the NPP’s established democratic processes and the importance of choosing candidates best positioned to secure electoral success. He dismisses claims of tribal or religious motivations behind Kufuor’s selection, emphasizing that such accusations misrepresent the party’s internal dynamics and commitment to meritocracy. The shift in support from Adu Boahen to Kufuor, according to Opoku, reflected the delegates’ assessment of who was best equipped to lead the party to victory in the 1996 elections, given the prevailing political climate and the lessons learned from the 1992 outcome. This perspective underscores the inherent fluidity of political strategy and the need for parties to adapt to changing circumstances.

The assertion that Adu Boahen’s loss stemmed from identity politics is further challenged by Opoku, who frames such claims as “emotional blackmail tactics” intended to manipulate public sentiment and circumvent genuine political competition. He argues that such accusations detract from a healthy democratic process, which relies on open competition and collaboration after the contest. Opoku emphasizes that the NPP’s focus remains on choosing the candidate most likely to win the general election, a pragmatic approach necessary for any political party seeking power. He suggests that attributing losses to identity politics undermines the importance of strategic decision-making and the need to evaluate candidates based on their suitability for national leadership.

Opoku underscores that the NPP’s internal processes are driven by a collective desire to win elections, necessitating a thorough evaluation of each candidate’s strengths and weaknesses. This assessment encompasses a range of factors, including the candidate’s ability to connect with the electorate, articulate a compelling vision, and build a broad base of support. He emphasizes the importance of avoiding divisive narratives based on identity, which he believes distract from the essential task of selecting the most qualified candidate. Opoku portrays the NPP as a party driven by a pragmatic approach to winning elections, prioritizing the candidate’s potential to secure national victory above all else.

In conclusion, the shift in NPP support from Adu Boahen to Kufuor in the 1996 elections reflects the dynamic nature of political competition and the importance of strategic decision-making within parties. While some may attribute this change to factors related to identity, Opoku firmly rejects such claims, emphasizing the NPP’s commitment to selecting candidates based on merit and their perceived ability to secure electoral victory. He criticizes attempts to exploit identity politics for sympathy as detrimental to healthy democratic competition, reiterating that the NPP’s primary focus remains on selecting the candidate best positioned to lead the party to national success. The narrative surrounding Adu Boahen’s role in the NPP, therefore, should be understood within the broader context of the party’s evolving strategies and its unwavering focus on winning elections.