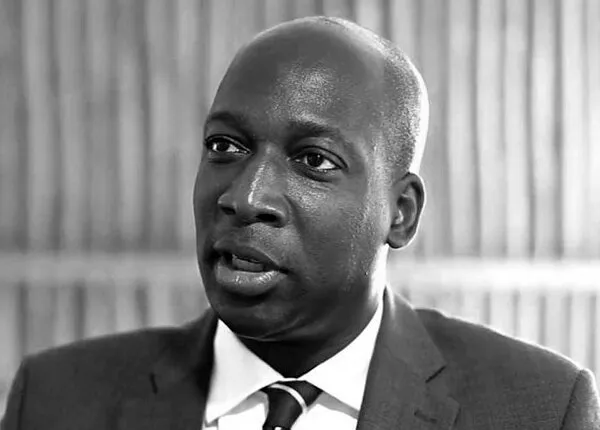

The Bank of Ghana’s (BoG) policy imposing strict term limits on CEOs and Managing Directors (MDs) of regulated financial institutions has sparked a heated debate, with critics questioning the necessity and efficacy of such a directive. Yaw Nsarkoh, a prominent business leader and former Executive Vice President of Unilever Ghana and Nigeria, has emerged as a vocal opponent of the policy, arguing that it disrupts leadership continuity and undermines meritocracy by forcing out high-performing executives. This policy, introduced in 2018 following a banking sector cleanup, mandates a maximum term of four years for bank chiefs, renewable for only two additional terms, regardless of performance. Nsarkoh contends that such decisions should be left to the discretion of the banks’ boards and stakeholders, not dictated by the central bank, labeling the policy as “intrusive legislation.”

The core of Nsarkoh’s argument lies in the principle of meritocracy. He believes that imposing arbitrary term limits prevents institutions from retaining highly effective leaders who have demonstrated consistent success and possess invaluable institutional knowledge. This forced exit, he argues, not only disrupts the bank’s strategic direction but also discourages long-term planning and investment in human capital. Furthermore, it undermines the authority of the boards, which are responsible for overseeing the management and performance of the institutions. By dictating leadership tenure, the BoG effectively usurps the board’s responsibility to evaluate and retain CEOs based on their individual merits and contributions to the institution.

Critics of the policy echo Nsarkoh’s concerns, emphasizing the negative impact on board autonomy and shareholder rights. They argue that boards are well-equipped to assess CEO performance and make informed decisions about their tenure based on the specific needs and strategic goals of the bank. Imposing a blanket term limit disregards the nuances of individual situations and the potential for exceptional leadership to drive sustained growth and stability. Moreover, shareholders, who ultimately own the banks, are denied the opportunity to retain leaders who have delivered strong returns and fostered a positive corporate culture.

Professor H. Kwasi Prempeh, Executive Director of the Ghana Center for Democratic Development, adds another dimension to the debate by questioning the legal basis of the BoG’s directive. He suggests that the policy oversteps the central bank’s authority and infringes upon the rights of banks to manage their internal affairs. Prempeh challenges the banks to contest the regulation in court, arguing that such a legal challenge could clarify the boundaries of the BoG’s regulatory powers and protect the autonomy of financial institutions.

The debate underscores the tension between regulation and autonomy within the banking sector. Proponents of the term limits may argue that it serves as a safeguard against potential abuses of power and promotes leadership renewal. However, critics contend that the policy’s rigid structure fails to account for individual performance and institutional context. They advocate for a more nuanced approach that empowers boards to make informed decisions about CEO tenure, based on merit and the best interests of the institution.

The call for a review of the BoG’s policy grows louder as stakeholders argue for a shift towards leadership policies grounded in trust, meritocracy, and global best practices. They believe that allowing boards to exercise their judgment in evaluating and retaining CEOs will foster a more dynamic and competitive banking sector, ultimately benefiting the Ghanaian economy. The debate raises fundamental questions about the optimal balance between regulatory oversight and institutional autonomy, and its resolution will have significant implications for the future of Ghana’s financial landscape.