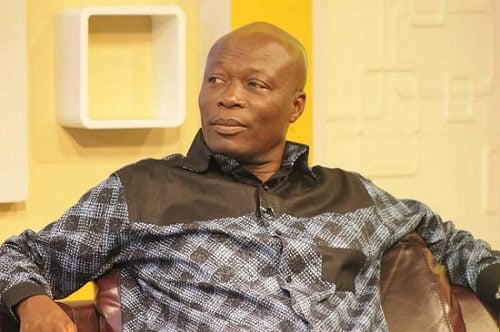

The Ghanaian government’s recent implementation of a GHS1 per litre fuel levy has sparked debate and concern among citizens. Nii Lantey Vanderpuye, National Coordinator of the District Road Improvement Programme (DRIP), has stepped forward to defend the levy, arguing that it represents a crucial measure to avert a potential 50% increase in electricity tariffs and a resurgence of the dreaded “dumsor,” the term used locally to describe power outages. He frames the levy as a preemptive strike against a looming energy crisis, a necessary sacrifice to prevent a far more damaging blow to the economy and the well-being of Ghanaians. Vanderpuye insists that the alternative to the levy is a steep hike in electricity costs, a burden he believes would be far more onerous on the population.

Vanderpuye emphasizes the genesis of the current energy sector challenges, attributing them to collective national actions and decisions. He suggests that the financial pressures facing the energy sector are a consequence of past choices and that the levy is a necessary corrective measure to address the resulting imbalances. He presents the levy as a shared responsibility, emphasizing the collective nature of the problem and the need for a collective solution. The logic presented is straightforward: the levy is an investment to prevent a larger financial burden on consumers through increased electricity tariffs. He posits that contributing a small amount through the levy is preferable to absorbing a significantly larger cost in the form of higher electricity bills.

The core argument hinges on the premise of choosing between two undesirable options: increased taxes via the fuel levy or increased electricity tariffs. Vanderpuye argues that the government, faced with this dilemma, opted for the lesser of two evils by implementing the levy. This approach, he contends, prioritizes mitigating the immediate financial impact on consumers while simultaneously addressing the underlying financial challenges within the energy sector. By generating revenue through the levy, the government aims to stabilize the energy sector and prevent a domino effect that could lead to higher tariffs and ultimately, the return of debilitating power cuts.

The justification for the levy rests heavily on the precarious financial state of Ghana’s energy sector. Vanderpuye paints a picture of an industry under immense financial strain, struggling to meet its obligations and maintain a stable power supply. The levy, in this context, is presented as a lifeline, a necessary injection of funds to prevent the system from collapsing under the weight of its financial burdens. The implication is that without the additional revenue generated by the levy, the energy sector would be unable to function effectively, leading to inevitable price hikes and disruptions in power supply.

The government’s strategy, as articulated by Vanderpuye, focuses on long-term stability and sustainability within the energy sector. The levy, he argues, is not just a temporary fix but a strategic investment in the future of the energy sector. By addressing the current financial shortfall, the government aims to create a more robust and resilient energy infrastructure, thereby safeguarding the country from future power crises. This long-term vision is contrasted with the short-term pain of the levy, presenting it as a necessary sacrifice for a more secure energy future.

In essence, Vanderpuye’s defense of the GHS1 fuel levy is built on the argument of preemptive action and damage control. He portrays the levy as a difficult but necessary step to prevent a more severe economic fallout in the form of significantly higher electricity tariffs and the return of power outages. He frames the decision as a choice between two undesirable outcomes, with the levy representing the lesser of two evils. The overarching narrative emphasizes the levy as a collective contribution towards a more stable and sustainable energy future for Ghana, a necessary investment to prevent a larger and more disruptive crisis.